You have probably heard of a shooting or falling star, but have you ever seen one? If you have ever spent any amount of time looking up at the night sky, then you probably have – a flash of light streaking high above through the darkness for just a moment, disappearing just as quickly as it appeared – sometimes so quick that you cannot be sure if you have really seen something or imagined it. You might think that your eyes are playing tricks on you, but shooting stars are definitely real! Your parents may have told you to quickly make a wish on a shooting star before it vanishes – what will your next wish be when you get to see one?

Here’s another question for you, a little bit harder this time: do you know what a shooting star is? Their names are a little misleading and this causes some people to think that these fast moving trails of light really are stars that have fallen out of the sky. However, this is not true. Our Sun is a star, our closest star, and the other stars are many many miles away (it would take more than your lifetime to travel to them!) and since they are much bigger than a shooting star, they are certainly not responsible, so we can count them out. If you are still not sure of the answer, then you might be surprised to learn that shooting stars are just tiny bits of dust entering the Earth’s atmosphere from space. Tiny particles, like grains of sand or pebbles on a beach, like to crash into the atmosphere at amazingly fast speeds – some faster than a car travelling at his highest speed along the motorway! But don’t worry – they are not big enough to harm you! If you pick up a stone from the beach, however, you will find that a fast moving pebble does not quite look the same as a shooting star, no matter how hard you throw it. This is because the light that you see is the heat of the air around them as they fly into the atmosphere and burn up.

Sometimes something a little bigger than a pebble will shoot through the atmosphere and we seem them as fireballs – if you are lucky enough to see one of these then you might see flames shooting from it! But don’t worry, fireballs are not dangerous – like shooting stars, they are high above us.

Occasionally, however, the piece of rock can be big enough so that it does not all burn up while entering the atmosphere and it will hit the ground. We call these meteorites (while they are flying through the atmosphere as shooting stars we call them meteors, and while they are in space we call them meteoroids – it is important to remember the difference!). A whopping 38,000 meteorites have been found on Earth so far, from all over the world, but most are found in the hot desert or in freezing cold Antarctica. You may have heard stories of someone you know that has found a meteorite or maybe you have even found one yourself! If you have never had the chance to touch or see a meteorite, then you might not know that these space rocks are quite different to the ones that you are likely to find in your backyard, but not in the way that you might think.

Image courtesy of Lunar and Planetary Institute

This map shows some of the locations in Antartica where many meteorites have been found.

There are three main types of meteorites: stony, iron and stony-iron. A lot of them have been smashed off from very large chunks of rock, called asteroids, in collisions before eventually finding their way to our planet. Iron meteorites, for example, are bits of metal iron cores of large asteroids that were once hot enough to have melted, causing all of their iron to sink to the centre. Stony meteorites look most like the stones that you find on Earth and come from the outer layer of asteroids, whereas stony-iron meteorites are a mixture of the two.

.jpg)

Image courtesy of NASA Johnson Space Center

This meteorite came from the moon.

Comets and asteroids are leftover debris from the when the planets were being built in the Solar System. Just like asteroids, comets make falling stars, but rather than seeing one of them every so often (that are easy to miss!), there is a shower of them – astronomers call these meteor showers and they are made when the Earth moves through the tail of a comet that has been left behind after one of these icy and dusty bodies have swooped past us. You can usually see at least a few meteors during a shower, but on a particularly good show, you can sometimes see hundreds of shooting stars per hour – you can be sure not to miss one then! The best meteor showers are the Quadrantids that are at their best on the 3rd January every year, the Lyrids that are at their best on 22nd April, the famous Perseids on 12th August, the Orionids on 22nd October, the Leonids on 17th November and the Geminids on 14th December. The Geminids, it is thought, are actually dust from an asteroid called Phaethon rather than a comet – and it has been shown that Phaethon was originally part of the second biggest asteroid Pallas, but was smashed off in a mighty collision with another asteroid billions of years ago. Meteor showers are named after the constellation that they appear to be falling from. For example, the Geminids will be shooting away from the constellation, Gemini (The Twins), whereas the Perseids are from Perseus (The Hero). Why don’t you grab a map of the constellations and, with your friends, see if you can find them in the night sky before the meteor showers start?

So, ready to go meteor spotting? Check out the box, How to watch a meteor shower, to find out how!

Image: NASA

How to watch a meteor shower Watching a meteor shower can be one of the most enjoyable things about observing the night sky, waiting with tense excitement to see the next shooting star. The best meteor shower is the Perseids – not just because it has the most meteors (although it does have as many as 100 per hour) – but because you can sit out in the garden during the warm summer night to watch them, rather than having to wrap up in your scarf, bobble hat and wooly mittens during the middle of winter, as you would have to for watching the Geminids in December!

For the best meteor viewing, it is best to find a dark corner of your garden or from wherever you are observing them. Give time for your eyes to get used to the darkness, and use a red light flashlight rather than a normal flashlight, so that you do not ruin your night vision when looking at maps of the night sky. If you do not have a red light flashlight, then you can just cellotape some red see-through paper over a normal flashlight – it works just as well! To avoid going back inside, bring a water bottle and some snacks out into the garden with you. Make sure that you wrap up warm – even in August for the Perseids, it can still get chilly late at night. Remember that a hat is essential, as your body loses much of its heat through your head. Now, you have probably found that when looking at the stars that straining your neck to look up all the time can quickly become uncomfortable. For meteor watching, a deck chair is ideal – you are angled comfortably so you do not have to strain your neck.

Simply watching for meteors and counting up how many you see in your head is fun, but if you want to be a proper scientist then you need to record your results, as you would during a real science experiment. With a clipboard, pen and paper, write down the time that you see each meteor, in which direction the meteor comes from, its colour (if you can see any colour!), and how bright it was compared to other stars in the constellations that surround it. Remember that a star map will be able to help you with how bright certain stars are in a constellation.

|

|||

So you’ve spent some time out in the garden, watching and recording meteors. What do you do with your results then? Some scientists can use your results, such as those at astronomical associations, and they will look for trends in the meteor shower – for example, were they more or less active than in previous years? If so, why? If you are unsure of who to contact, you should ask your teacher or parents to help you. Who knew that by watching a meteor shower and reporting what you see could allow you to contribute to real life science! How exciting is that?!

Near the Grand Canyon in Arizona is Meteor Crater (above). It was formed about 50,000 years ago when a meteor about 30 meters wide and weighing 100,000 tons struck the Arizona desert at an estimated speed of 20 kilometers per second (12 miles per second). |

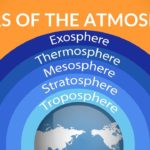

The point in the sky where a meteor shower originates is called the radiant point. It is much like the center of a bicycle wheel with the meteors radiating outward from the center. During a meteor shower, the radiant point will move across the sky as the Earth continues to rotate. Keep reading below to see all the different meteor showers that occur during the year, and learn how the showers got their names.