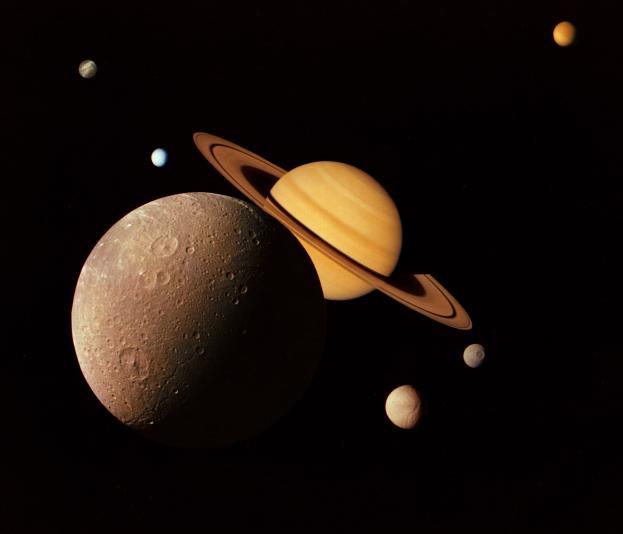

So who was lucky enough to spot Saturn’s rings in the first place? Stepping back to 1610, astronomer Galileo Galilei was the first person to see them through his telescope. However, at the time, his telescope was not strong enough to see details and he therefore did not realize that what he saw were rings around the planet and, ever since his sightings, early astronomers wondered what they could be.

In 1655, amazed by what Galileo saw, Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens suggested that Saturn had a disc surrounding it. To get an idea of what Huygens described imagine a Pogo Ball – they are bouncy balls with a disc around them – you might have one in your garden or your parents might have had one when they were little. If you don’t have one on hand, why not get a football (soccer ball) and cut out a disc to make your very own Saturn!

You may have noticed that we prefer to use the word “rings” rather than Huygen’s idea of a disc. The reason behind this is because rather than being similar to a frizbee with a hole in the middle, Saturn really does have ring-like structures around it and astronomers have given a name to each of them as well as the gaps that separate them.

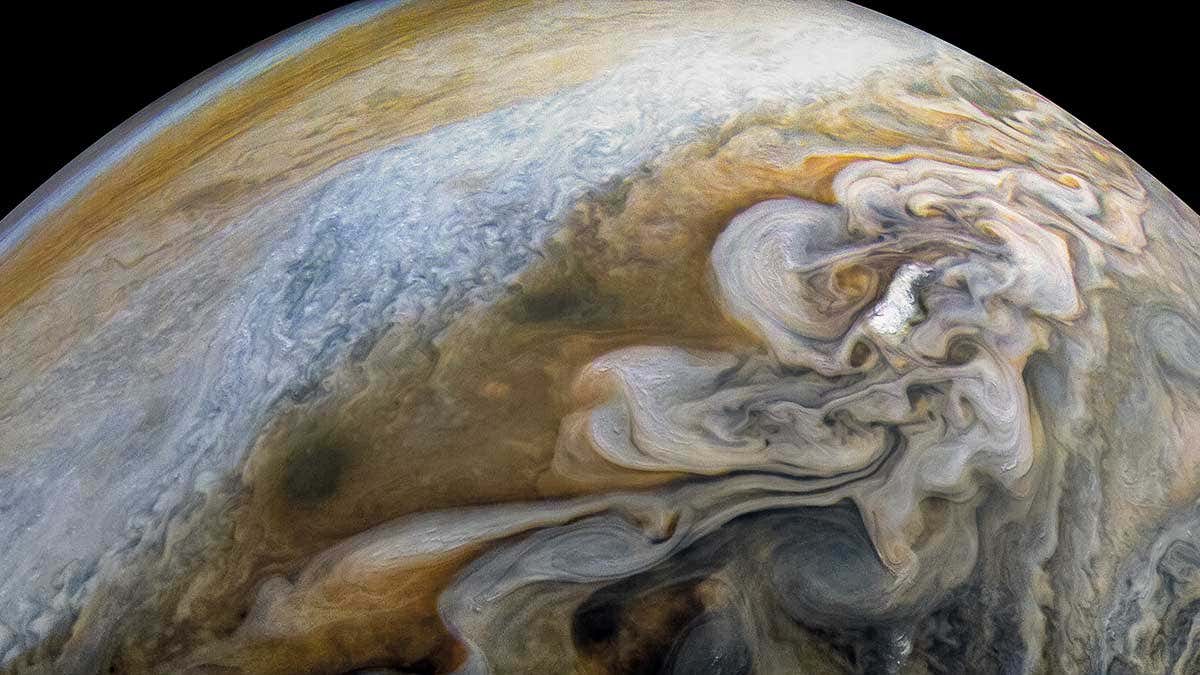

Image: NASA

There are 7 rings in total and, as expected, they are named in the order they were discovered. Because they are named in an ordered system, astronomers have named the rings as letters such as Ring A, Ring B and Ring C all of the way up to Ring G. While you might think that the names of these rings are quite boring, they helped astronomers refer to them quickly and easily – after all, Saturn’s rings are quite complicated! So we have got some rings, what do we call the spaces in between them? That’s right – they’re called gaps and while you might think that these are going to have even duller names, think again! Scientists decided to have a bit more fun naming those! Before you carry on reading about them, maybe have a think about what you would call the rings and gaps if you were asked to name them!

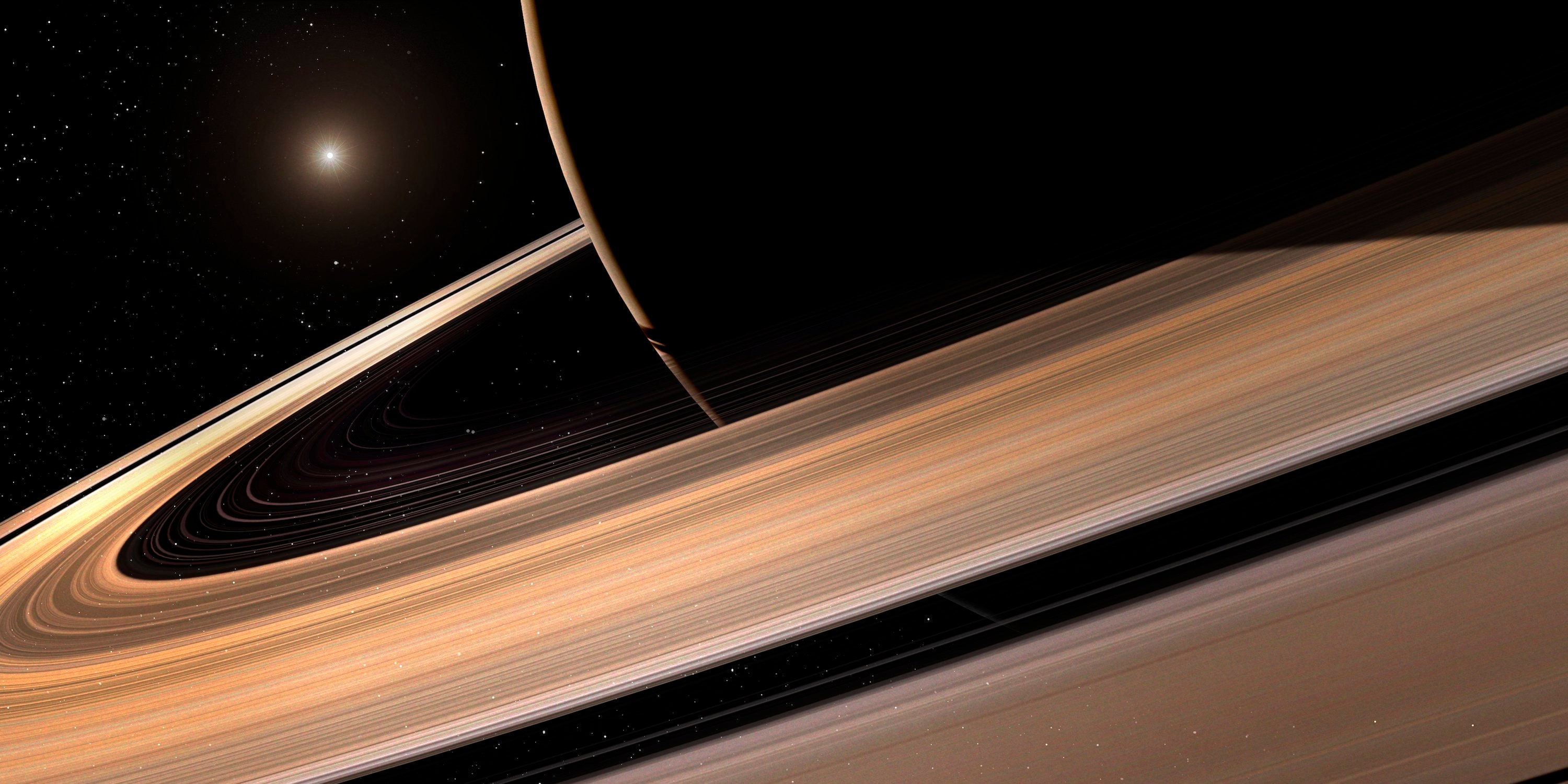

Now let’s learn about the gaps. You have probably noticed them in a picture that you have looked at of Saturn – but you wouldn’t be the first to spot them! Back in 1795 Giovanni Cassini, an astronomer (who now has a mission named after him called Cassini) saw a large obvious gap which we now know as the Cassini Division. This gap is gigantic – it would be pretty much impossible for you, or even your parents to be able to jump over it! Near the edge of the rings is another gap that we now refer to as the Encke gap. How do you think that this gap got its name? That’s right! It was named after its discoverer Johann Encke – a German astronomer.

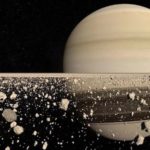

Image: NASA/JPL Space Science Institute

So how do you think that gaps like these were made? Have a guess before you watch the video below to find out!

Watched the video? If you have, then it’s time for a small test! If you imagine for a moment that you are an astronomer back in the times of Cassini, then the next question that you would have wondered, as soon as the disc was uncovered, was: what is this disc made of? Do you remember from the video that you have just watched?

That’s correct – the rings are made mostly of pure water ice (the frozen water that you’re very likely to find in the fridge). But that’s not all – there’re some lumps of rocks that scientists call tholins and silicates in there too. As mentioned, the rings are not solid and that means that there must be more gaps in the rings – we just can’t see them from Earth. With the help of missions to Saturn (such as Cassini and Voyager), we have been able to see lots of other spaces in the rings. Below is a table that shows the main ones – why not cover up the first column and have a go at guessing what the name of the gaps are by using the “Named after” column as a clue?

Name |

Distance from Saturn (miles) |

Width (miles) |

Description |

Named after |

|

D Ring |

41,570 – 46,298 |

4,660 |

Faint innermost ring made of smaller rings. |

None |

|

C Ring |

46,390 – 57,166 |

10,874 |

Wide faint ring made of dark material |

None |

|

B Ring |

57,166 – 73,061 |

15,845 |

Largest and brightest of the rings. Has spokes and an embedded moonlet (S/2009 S1). |

None |

|

Cassini Division (Gap) |

73,061 – 75,913 |

2,920 |

Gap between A Ring and B Ring. The Huygens Gap is at the edge of the Cassini Division. |

Giovanni Cassini |

|

A Ring |

75,913 – 84,988 |

9,072 |

Contains the Encke Gap, Keeler Gap and many moonlets discovered by the Cassini spacecraft. |

None |

|

Roche Division (Gap) |

84,988 – 86,607 |

1,616 |

Separates the A Ring and the F Ring. |

Édouard Roche |

|

F Ring |

87,104 |

19-311 |

Active ring with features that change every few hours. |

None |

|

Janus/Epimetheus Ring |

92,584 – 95,691 |

3,107 |

Faint dust ring around the region occupied by the orbits of Saturn’s moons, Janus and Epimetheus. |

Saturn’s moons Janus and Epimetheus |

|

G Ring |

103,148 – 108,740 |

5,592 |

Thin, faint ring that lies between the F ring and E ring. |

None |

|

Methone Ring Arc |

120,689 |

Unknown |

A faint ring arc thought to be made by dust ejected from impacts with Saturn’s moon Methone. |

Saturn’s moon Methone. |

|

Anthe Ring Arc |

122,823 |

Unknown |

A faint ring arc thought to be made by dust ejected from impacts with Saturn’s moon Anthe. |

Saturn’s moon Anthe. |

|

Pallene Ring |

131,109 – 132,663 |

1,553 |

A faint dust ring thought to be made by dust ejected from impacts with Saturn’s moon Pallene. |

Saturn’s moon Pallene. |

|

E Ring |

111,847 – 298,258 |

186,411 |

Outermost ring and extremely wide. |

None |

|

Phoebe Ring |

~2,485,485 – >8,077,826 |

None |

A disk of material close to the orbit of Saturn’s moon, Phoebe. |

Saturn’s moon Phoebe. |

Remember that “~” means “around” or “approximately” and “>” means “greater than”

or “more than”.